Photo: Designua/Shutterstock.com

The menstrual cycle involves a carefully orchestrated symphony of hormonal fluctuations, and unfortunately, many women experience unpleasant symptoms leading up to or during menstruation. A deeper understanding of the different phases of the menstrual cycle offers the opportunity to use nutrition as a strategy to support hormone health.

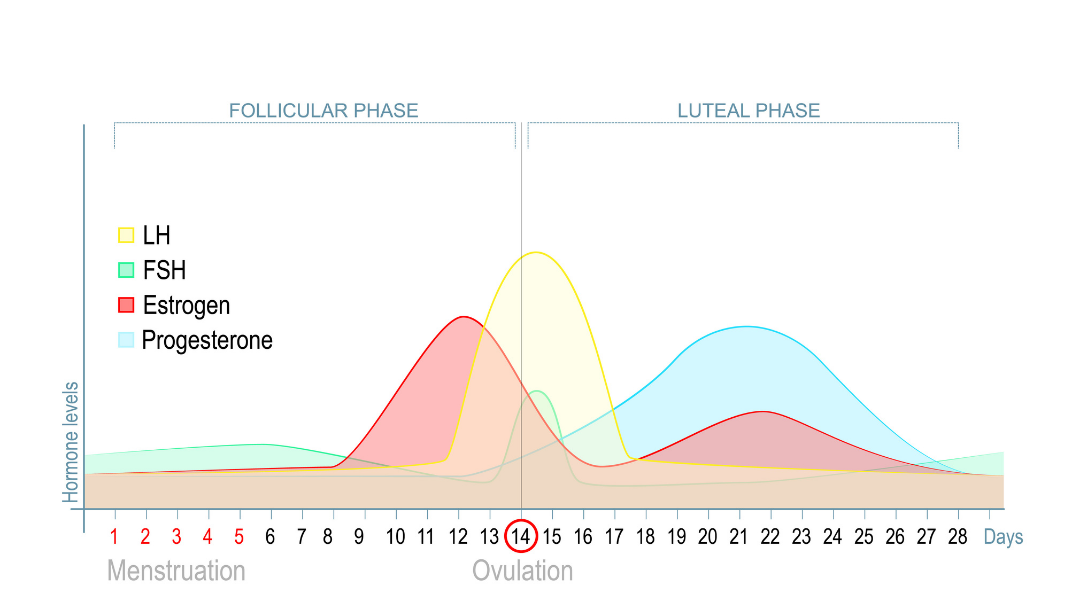

The menstrual cycle is split into the follicular and luteal phases. The early follicular phase, during which menstruation takes place, is characterized by low levels of estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen reaches its peak during the follicular phase, and a surge in luteinizing hormone signals ovulation. The cycle then enters the luteal phase during which estrogen increases by a lesser degree, and progesterone reaches its peak. Both hormones begin to decrease nearing menstruation, and the cycle repeats itself.

There is plenty that can go awry during this process. Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is very common and can include symptoms such as emotional dysregulation, bloating and fluid retention, fatigue, and breast tenderness. Women also may experience dysmenorrhea, which is characterized by painful cramping just before or at the beginning of menstruation.

Dysmenorrhea is thought to occur due to the presence of inflammatory prostaglandins and leukotrienes, which contribute to uterine contractions, increased nerve sensitivity, and a lack of muscular blood flow. Prostaglandins are higher in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase. Nutrition can be tailored to address prostaglandin synthesis and decrease the prevalence and severity of menstrual symptoms.

Inflammation and Nutrition

PMS and/or dysmenorrhea may be connected to oxidative stress and inflammation. Women with dysmenorrhea can have upregulated genes related to inflammatory cytokine production as well as higher oxidative stress markers and lower antioxidant status.

The BioCycle study, a study of 259 healthy women, showed that oxidative stress was associated with the severity of PMS symptoms, such as food cravings and crying spells. Higher vitamin A levels were associated with decreased cramps, bloating, and swelling in hands or feet, and higher γ-tocopherol, a form of vitamin E, was also associated with less swelling. Increased levels of vitamin A and α-tocopherol, another form of vitamin E, were associated with the hormones testosterone and estradiol. Researchers also found that antioxidants such as vitamin C and α-tocopherol, and compounds such as beta carotene and lycopene, were lowest during menstruation.

Micronutrient levels also fluctuate throughout the cycle. In one study, inflammation was highest in the early follicular phase, while average concentrations of zinc decreased by 6.6%, and magnesium decreased by 4.6% from the early follicular phase to the luteal phase. Among the study participants, magnesium deficiency was significantly more prevalent in the middle of the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase (29% to 49%). This was hypothesized as relating to variations in estrogen. The concentration of ferritin also decreased as the cycle progressed, and anemia was found to be at its highest in the middle of the cycle.

A study using Korean red ginseng reported a decrease in oxidative stress with women experiencing improvements in menstrual pain and irregularity. Korean red ginseng has been found to influence estrogen receptors and gene activity. In this study, it also helped to facilitate detoxification of bisphenol A (BPA), a toxicant that can increase reactive oxygen species in the body. Changes in BPA concentrations were seen as early as four days into the supplement regimen.

A systematic review found the consumption of fruits and vegetables, as well as fish rich in omega-3 fatty acids, was associated with less menstrual pain. Fruits and vegetables can be rich sources of magnesium and calcium, which reduce prostaglandin synthesis, as well as positively impact nerve activity. Fruits and vegetables are also a good source of dietary fiber, which was found to be negatively associated with dysmenorrhea. In the same review, sugar consumption was significantly associated with dysmenorrhea, and skipping breakfast was positively correlated with the intensity of symptoms.

Supplementation with iodine, selenium, and gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), an anti-inflammatory omega-6 fatty acid, led to improvements in breast pain and fibrocystic nodules after three menstrual cycles. Women who typically relied on pain medications to manage their breast pain experienced a 50% reduction in pain medication use. These nutrients were chosen for the study due to their effects on estrogen and thyroid hormone metabolism.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D receptors are found in the ovaries and uterus, making vitamin D an important nutrient to consider when it comes to supporting a healthy menstrual cycle. A systematic review found that vitamin D levels begin to increase during the follicular phase. Two studies within the review reported that vitamin D levels can also rise in the luteal phase, although more research needs to be done to fully confirm the fluctuations of vitamin D throughout the cycle.

Researchers have found that lower vitamin D levels are associated with an increased likelihood of having an irregular cycle. A study of nearly one thousand adolescent girls found an improvement in menstrual symptoms when study participants were given high-dose vitamin D supplements for 9 weeks. Before the intervention, 85.3% of participants were vitamin D deficient. Supporting vitamin D levels caused the prevalence of PMS combined with dysmenorrhea to decrease from 32.7% to 25.7%, and the prevalence of PMS to decrease from 14.9% to 4.8%. Symptoms such as crying spells and backaches also decreased. This change in symptoms is thought to be due to the reduction of prostaglandins by vitamin D. Supplementation also increased the percentage of participants who experienced normal lengths of menstruation and overall cycles.

Curcumin is known for its anti-inflammatory properties and can influence vitamin D receptor activity. A group of women with PMS and dysmenorrhea received daily curcumin supplementation for seven days before menstruation and for three days afterward. After three menstrual cycles, vitamin D levels were significantly higher than the placebo group, and levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and bilirubin, two liver markers, were decreased.

Metabolism

The menstrual cycle is an energy-dependent process, and adequate energy intake is an important consideration for supporting regular cycles. The REFUEL study looked at the effect of increasing energy intake in athletic women who either had irregular/infrequent menstrual cycles (oligomenorrhea) or amenorrhea. An increase of about 330 calories per day helped to restore the menstrual cycle, and the majority of women experienced improvements after six months of this intervention. Of note, 79% of study participants exercised recreationally (rather than competitively) but found benefit in increasing their caloric intake in order to support their hormone health.

Energy expenditure and caloric requirements differ throughout the menstrual cycle. A systematic review found that resting metabolic rate, or the number of calories your body burns at rest, may be higher during the luteal phase.

A small study of five women looked at the requirements of the amino acid lysine across the menstrual cycle. There was a higher lysine requirement during the luteal phase, and researchers postulate that this may be due to greater levels of amino acid breakdown. Other studies have also explored higher amino acid oxidation during the luteal phase due to progesterone’s catabolic effects. In addition to making sure you are consuming adequate calories throughout the month, energy and protein demand may be even higher in the second half of the cycle.

Seed Cycling

Seed cycling has been widely discussed on blogs and podcasts and is touted for its ability to facilitate hormone balance. Briefly, seed cycling involves the consumption of particular seeds during the follicular and luteal phases. Typically, pumpkin, flax, sesame, and sunflower seeds are used.

It is difficult to find published studies on the specific associations between these seeds and female hormones, let alone on the comprehensive seed cycling protocol itself. However, there are studies exploring the benefits of these seeds for various conditions related to inflammation and hormone metabolism. For example, flaxseed is used in seed cycling to support estrogen metabolism since flaxseed lignans act as estrogen antagonists in cycling women. A mixture of ground sesame, pumpkin, and flaxseeds improved inflammatory markers as well as metabolic markers such as triglycerides, insulin, and glucose in patients on hemodialysis due to the anti-inflammatory fatty acids and antioxidants present in the seeds. Sesame seed lignans increased antioxidant capacity and improved fatigue in a group of adults who experienced daily fatigue. Pumpkin seeds are rich in magnesium and zinc, and as we previously explored, these nutrients may decrease throughout the menstrual cycle.

While seed cycling may be anecdotally helpful, there is a need for more research on the topic.

Closing Thoughts

- Antioxidant nutrients are important for protecting against oxidative stress and may be lower during menstruation. Focus on consuming plenty of brightly colored fruits and vegetables during the luteal phase and early follicular phase in order to address prostaglandin synthesis and support antioxidant status.

- Nutrients such as zinc, magnesium, omega-3 fatty acids, and vitamins C and E can help support healthy menstrual cycles. During the luteal phase, include dietary sources of zinc and magnesium to prepare for a nourished follicular phase. Zinc can be found in foods such as oysters, grass-fed beef, and chickpeas, while pumpkin seeds, chia seeds, spinach, and almonds contain magnesium.

- Vitamin D is an important nutrient for female hormone health. Testing your levels can provide valuable insights into the need for supplementation. During spring and summer, spending more time outdoors can help to support vitamin D levels. You can also find vitamin D in some foods such as salmon, sardines, mushrooms, and fortified milk.

- Pay attention to protein intake during the luteal phase and incorporate sources of leucine. This amino acid can be found in foods such as cheese, beans, chicken, turkey, pork, beef, and some fish. Be sure to choose high-quality proteins from pasture-raised, grass-fed, or wild-caught sources whenever possible.

- You may benefit from a modest increase in caloric intake during the second phase of the menstrual cycle due to an increase in metabolic demands.

- While seed cycling is a popular topic and may be useful for some women, there is a need for further research on the benefits of using seeds as an intentional strategy to promote female hormone balance.

If you plan to incorporate more colorful, plant-based, and/or whole foods into your daily eating; have food allergies or questions about which foods can best support your health and menstrual cycle; or have questions or concerns about your menstrual cycle, talk to your doctor, nutritionist, dietician, or another member of your healthcare team for personal options based on your individual circumstances. There are certain medications that may interact with plant-based foods.